From children placing phones in empty crinkly crisp bags, to outright ‘bans’ and gender-based rules, there is no one smartphone school policy that fits all. At our workshop with secondary school educators in November, we found that most are finding ways to manage students’ smartphones in schools that take into consideration the needs of students and teachers.

Educators from all over the UK and abroad joined the DFC’s researchers to learn more about the research on smartphone policies in schools, based on the recently launched DFC review of the latest evidence, and to explore how to design child rights respecting smartphone policies. The outcome highlighted the complexities schools face when designing school smartphone policies and the diversity of issues that the educators were trying to address. Our conclusion is that there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution, as we will explore further here.

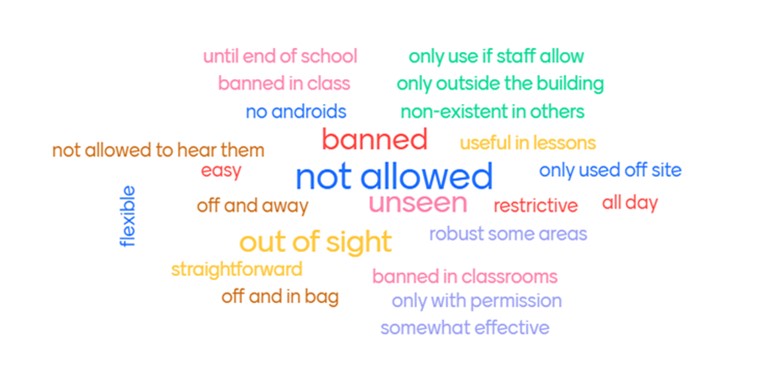

When asked to describe their schools’ smartphone policies in a few words the educators answered the following in a workshop poll.

A more thorough survey was filled out by the 69 registered participants, revealing the broad range of policies schools have implemented.

|

Policy

|

Description

|

|

Complete ban

|

No phones on school premises.

|

|

‘Off and away’

|

These policies allow students to bring phones to school, but they must be kept off and out of sight for the entire school day. Responsibility is placed on the students to manage their phones.

Variation: some allow students to use phones if teachers have given permission.

Variation: some allow use in the classroom, when teachers request students to use their phones for schoolwork.

Sanctions: some implemented escalating sanctions if students are found in breach of the off and away rule.

|

|

Stored away

|

These policies allow students to bring to phones to school, but they will be stored away during the school day by teachers (in a box in the classroom, in a school office etc.). Responsibility is placed on teachers to manage phones.

Variation: a few mentioned the use of Yondr pouches.

|

|

Permissive

|

These policies allow students to bring phones in school, they are allowed to be used outside of class but cannot be seen or used during class.

Variation: Some seniors, especially GCSE's and A-levels, have no restrictions whereas earlier years have more restrictive rules.

|

|

Age differentiated (increasingly permissive)

|

These policies differentiated between primary and secondary school students. Primary school students would typically have more restrictive policies, including outright bans. In secondary school the policies became increasingly more permissive, as students were expected to better be able to manage their phones.

|

|

Gender differentiated

|

One example of gender differentiated policies was related from two gender exclusive schools within the same school academy.

|

|

No policy

|

A few schools had not implemented an official policy, but did nonetheless exercise ways of managing students’ phone use in schools, such as confiscating them if disruptive.

|

Different rationales for implementing smartphone policies

Many of the educators we met expressed that smartphones were not a problem in their schools, yet they still felt there was pressure to implement stricter smartphone policies. While others described a variety of problems related to students’ smartphone use in schools that had prompted more restrictive policies. The rationale related to schools’ reasoning behind smartphone policies also differed. For some, the motivation was primarily social and for others, it was primarily academic.

For some smartphones were seen as a distraction in class, but others were more concerned about the academic implications of phone distraction outside of school, such as students watching TikTok at night and not getting enough sleep. Likewise for distractions during break times, where some pointed to problems with phones during breaks, whereas others did not report this as a problem. For some, the school’s tech was seen as more of a distraction during class than phones, as students managed phones without a problem, but used school laptops to message others, play games or even gamble during class.

There were different school rationales for their smartphone policies.

Safeguarding-restrictive policies

- Cyberbullying during school hours was mentioned by some as a motivation to establish more restrictive school policies, as teachers spent time investigating these instances. However, some argued that students can still message one another on school devices, such as through chat functions using school provided devices and EdTech.

- Students had filmed teachers during class or when having disagreements with students, they had also filmed other students in inappropriate ways and uploaded the content to the internet.

- Students carrying smartphones to school was seen as a risk as they can be robbed.

Safeguarding-permissive policies

- Allowing students to bring their smartphones to school, but keep them out of sight, was important to ensure students safety going to and from school.

- To support positive socializing in schools: more restrictive policies meant students were no longer using phones during breaks but socializing with peers.

- Improving student teacher relations: as teachers described having had to deal with telling students to put phones away at the beginning of class, creating conflict in the classroom.

- Academic reasons: included minimizing distractions in class as well as between classes. However, some teachers mentioned students using smartphones to cheat, for instance by using AI.

The range of schools represented by participating educators were evidence of the difficulties in issuing broad recommendations on the specifics of smartphone policies. Some examples included:

- Schools ranged in size, some were very large with up to 2’400 students, for a school of that size, alternatives like teachers collecting phones would be unfeasible.

- Some schools had students having to travel quite far, while others didn’t have this issue, meaning they were not equally concerned with the need to have a phone going to and from school.

- Some schools had primary and secondary schools and found that the policies that work for younger children are not feasible or appropriate for older students. They discussed a progression from restrictive to permissive smartphone policies as students get older and deemed capable of keeping phones off and away but also using them for particular educational purposes. For instance, one school enforced a smartphone ‘ban’ (no phone on school premisses) up until the age of 14 yet mentioned that parents worried about their children travelling across the city to school without a phone.

- Schools also varied in terms of the tech they had at hand. Some offered students their own devices, such as Chromebooks, whereas others had computer rooms for students to use. This meant that in some schools, smartphones could be a good option for in class activities that required searching for information or answering polls.

Although smartphone policies varied across the group flexibility was key to many educators' approaches to smartphones in schools. The different needs and skills of students were discussed not just based on age but also ability and needs, with several pointing out that some students need access to their phones for medical reasons and to regulate various conditions, and that policies need to take this into account.

Schools implement varying forms of enforcement policies the three-strike policy seemed the most common (three strikes and the phone is confiscated, needing to be retrieved by a parent).

Do teachers identify educational benefits to allowing smartphones in school?

Several educators described situations where they allowed students to use smartphones in class, this only included situations where teachers had given permission and asked students to use the phones for exercises, such as to complete polls. Older students were by many seen as capable of managing their phones and able to use them without supervision for schoolwork. However, some noted that this varied between classes, even in the same year.

For some educators allowing students to bring their devices to school, but keep them out of sight, was seen as an important way of educating students about responsible tech use, arguing that they will have their phones ‘out there in real life and need to learn to use them responsibly.’

Smartphones were also identified as potentially useful for outdoor schoolwork, allowing students to take photographs, look up species and more when doing schoolwork outside.

Are children and parents consulted when designing their smartphone policies?

Some schools had consulted parents, yet few had consulted students. One example of a school that had consulted students found that students wanted stricter policies than parents. One teacher described how they consulted parents who voted for a restrictive policy, yet ‘80%’ then asked for an exception to bring their phone to school. One of the main takeaways participating educators described wanting to bring back to their schools was that ‘we need to consult children.’

Features of good smartphone policies

In the workshop, educators identified a number of features needed to design child rights respecting school smartphone policies:

- Flexibility: based on age and the needs of individual students.

- Adaptability: ensure that the students' needs are met, using students’ smartphones alongside other devices for educational reasons could therefore be beneficial.

- Integration: managing smartphones responsibly in schools as a part of digital literacy.

- Reconciling different views: parents views on smartphones may differ from faculty and students.

- Comprehensiveness: policies that do not move the problem ‘elsewhere’ or create new ones (e.g. inequalities or bullying outside school). Policies need to take into account the relationship between school and home life.

- Child participation: children should be consulted (but they rarely are) to co-design policies that reflect responsible use, underscoring their agency.

- Information: Informing children and parents about smartphone policies and responsible smartphone use, is crucial. Explaining the rationale for the policy is crucial.

- Negative approaches don’t work: there is need for positive approaches that includes consulting and informing children in a positive way.

- Feasibility: the smartphone policies must be feasible and fair to students and faculty. The burden on teachers to manage smartphone policies need to be considered.

- Consistency: the importance of being consistent in applying the school policy was seen as important to social children effectively into adhering to the policy. Further, many pointed out that the policy needs to apply to everyone equally, all while being accommodating to individual needs.

Recommendations for further research

Among the highest ranked motivation among educators who registered for the workshop was to learn more about the current research and how this can inform better smartphone policies. The educators left us with recommendations for future research on smartphone policies, to further strengthen inform our research going forward. Recommending for the research community to further investigate:

- Policies’ implications for different groups of children, related to age, gender, socioeconomic status and special needs.

- Policies at different key school stages and how they fit into the broader school curriculum.

- Policies and their implications in a variety of schools with varying resources (e.g. concerning availability of tech, specialised teachers, socioeconomic setting and more).

Concluding observations

As our review of the evidence on school smartphone policies revealed, few studies have examined the effects of smartphone policies on academic performance and other outcomes. The school smartphone policies revealed in this workshop point to the broad range of issues and considerations that schools face when designing and implementing smartphone policies. Just like the evidence shows, the educators confirmed that nuance and flexibility in implementing policies are preferred over rigid and strictly enforced policies. They also confirmed research evidence suggesting that certain smartphone use in schools can be beneficial if carefully considered. Teachers and students, much like in available evidence, seem to favour restrictive smartphone policies, yet children are seldom consulted.

The workshop discussions revealed that educators are carefully considering both how smartphone use can be restricted, but also how they should be available for students in particular situations, as well as the possible benefits of using students’ phones for educational purposes. The list of ‘good features’ provided by the group discussions, captures the holistic and child rights-centred approach we encourage in our report “Smartphone policies in schools” found here.

Text authors: Kim R. Sylwander