- EdTech is processing children's data in schools and sharing their data beyond the school.

- The data processed about children is personal, even sensitive, and can reveal intimate details about them.

- Allowing data companies to harvest and use children's data infringes their rights to privacy, education and freedom from commercial exploitation. Children are unhappy with their data being collected.

- The burden on schools to negotiate contracts with opaque and powerful EdTech companies is unfair. School Data Protection Officers are often overwhelmed by the legal complexities and may be unaware of the scale of data processing.

- Based on extensive research, the Digital Futures for Children centre has developed a blueprint for child rights-respecting data governance.

See our latest project exploring the use of EdTech in UK schools.

Overview

Data-driven technologies are innovating rapidly, in complex ways. The data processed about children while they learn at school and elsewhere is personal, even sensitive. This has considerable implications for children's rights, as sharing children's data poses numerous risks, particularly as data governance is weak.

Schools' use of educational technology (EdTech) surged during the pandemic and continues to move at pace, with schools adopting EdTech for management, learning and safety. There has been insufficient consideration for the growing concerns about EdTech's lack of data protection compliance. Allowing data companies to harvest and use children's data infringes upon children's rights to privacy and freedom from commercial exploitation. This has potential adverse impacts on children's equity, inclusion, safety and wellbeing. Moreover, the claimed educational benefits of EdTech remain largely unproven.

Through a series of socio-legal investigations and interviews with schools, data protection officers and other experts, the DFC have evidenced the unfair burden placed on schools to negotiate contracts with EdTech companies, as they are mostly opaque and powerful companies.

Now that AI-driven EdTech is entering schools around the world, research, advocacy and policy must keep pace with business practices.

How children’s data are used at school

The DFC's UK-based interviews with data controllers, legal and data protection experts, found that:

- EdTech companies regularly display a lack of data protection compliance. Meeting the specific needs of children as data subjects improved when the UK's AADC came into force in 2021. However, whether and how this applies to EdTech companies or schools is mired in confusion.

- In the absence of regulatory clarity and compliance, EdTech companies have been able to collect and sell children's data to third parties, resulting in financial gain with little repercussion. Problems with data governance in UK schools, for example, showed that 92 commercial companies gained access to a child's data after he completed his homework on Vimeo. Many school data protection officers (DPOs) were unaware of the scale of data processing, particularly in the case of EdTech.

-

Establishing the scope of liability between contractual parties (schools and EdTech providers) is difficult. Under the UK GDPR, the data controller is responsible for deciding which data is processed, how it is processed, and for what purposes, while the data processor undertakes the actual processing activity. Both are accountable for data processing, but the controller's liability is greater. Even though most EdTech companies position themselves as data processors, their processing activities show that they act as data controllers.

-

DPOs struggle to comply with regulations due to the power and opacity of EdTech companies, as well as the complex responsibility boundaries. For example, a crucial complication arises when an EdTech provider offers optional features beyond those required for its core educational purposes, for then it becomes an independent data controller for non-core purposes. An example is the use of Google Maps alongside Google Classroom in a geography class. By clicking on Google Maps, the child unwittingly loses the data protection provided by Google Classroom, which allows Google Maps to harvest their data.

- According to UNESCO's (2023) Global Education Monitoring Report, big tech partnerships with schools give an unfair advantage to EdTech companies, as they subvert government oversight and overwhelm schools' competence to manage. Resultedly, companies gain a 'stranglehold on data' in ways that undermine privacy, safety, autonomy, equity and governance. This creates problems for education as the technology serves the interests of 'profit-seeking technology providers'. Government-led regulation, standards, accreditation and ethical procurement, as well as digital literacy and responsible business practices, are urgent.

Some European countries have challenged EdTech companies on their processing of educational data and privacy breaches, the Dutch challenge being the most successful. Such challenges could and should be taken on more widely.

What do children think of EdTech or know of its data sharing?

Children express concern over data sharing, yet they are encouraged to use EdTech in schools and lack information about safe data practices.

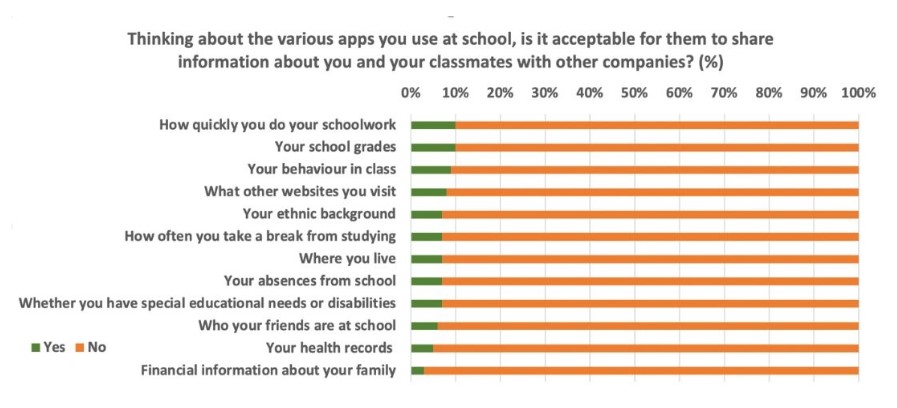

Results from a nationally representative survey showed that fewer than one in ten UK 6-17 year olds thought it acceptable for the apps they used at school 'to share information about you and your classmates with other companies.' Children's responses in a participatory activity with the DFC also reflected these concerns, stating that "apps have a responsibility not to leave data or personal information."

Further, while one in three 6- to 17-year-olds were asked by their school to use Google Classroom in 2021, only one in five children had their school discuss what information about them was kept by the apps or websites they used at school. Even fewer were informed about how their personal information was shared with the government and private companies, their right to correct such information or options to opt out of data collection at school.

EdTech infringes children’s rights

As stated by General comment No. 25 by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, Children’s rights apply at all times, including in relation to the digital environment.

We can frame the problems that EdTech causes with a child rights lens: EdTech risks infringing the right to privacy (Article 16, UN Convention on the Rights of the Child), education (Articles 28 and 29), and freedom from economic exploitation (Article 32).

Additional rights relevant to EdTech include non-discrimination (Article 2) – important given the costs of access and the biases embedded in AI, the best interests of the child (Article 3(1)), evolving capacity and parental responsibility (Article 5), freedom of expression, thought and assembly (Articles 13–15), access to information (Article 17), health (Article 24), rest, leisure and play (Article 31), protection from harm (Articles 19, 34, 36) and children's knowledge of their rights (Article 42).

Research conclusions

The evidence supports a compelling case for governments to better regulate the use of EdTech in schools. This case rests on four main arguments:

1. EdTech's processing and sharing of children's data in and beyond schools has very little oversight, in ways that infringe children's privacy and agency.

2. EdTech's significant power over data processing extends beyond specific breaches of data protection and competition law. EdTech may impact what education itself means, for example, by using insights gained from students to develop curriculum content and shape teaching and learning resources for schools. This is problematic as such companies may embed particular pedagogies (e.g., teaching to the test or 'right answer thinking') without the input or choice of educators.

3. Prevalent EdTech practices allow businesses to develop and test new products in public schools, risking the commercial exploitation of children while they learn.

4. The ways that EdTech undermines children's rights, in conjunction with the limitations of data governance, impede schools' capacity to protect their students, yet it is schools who are held accountable.

What should be done?

Our essay collection, featuring contributions from diverse academics and experts, examines how robust data governance can address the challenges of education data processing. It identifies novel approaches to data stewardship that could unlock new possibilities for sharing education data in children’s best interest and the public interest.

We bring these ideas together in a blueprint for child rights-respecting data governance and practice. For the UK, and perhaps other countries, we propose that:

1. Schools should only procure EdTech which routinely upholds the UNCRC (for instance, by conducting Child Rights Impact Assessment), complies with data protection regulations and is demonstrated independently to benefit children's education.

2. The regulator should develop an education-specific checklist to support schools, including identifying whether the school or EdTech company is the data controller.

3. The government should provide guidance and standard contract terms for schools on procuring EdTech products to relieve them of the heavy burden of contract negotiation with multiple EdTech providers, often involving an assessment outside their expertise.

4. This could be supported by a government certification scheme for EdTech, including an approved framework and standard EdTech assessment criteria to enable schools to identify products that protect children's rights and provide transparent and evidence-based pedagogical, safeguarding or administrative benefits.

5. Finally, the UK and other countries need a trusted data infrastructure for research, business, and government in children's best interests. This would specify which data can be made public and a public interest framework for data sharing.

What’s next - AI in EdTech

The DFC is examining how AI drives EdTech. In educational settings, AI is used to support teaching and assessment, for safeguarding, to personalise learning and for decision-making through the use of predictive analytics and adaptive systems. Such AI systems employ various techniques, including machine learning and large language models, such as generative AI (GenAI), which generates new content, including text, images, and videos.

As with earlier forms of EdTech, schools and other education settings are introducing AI-EdTech in advance of compelling evidence of benefit or transparent risk assessment.

Relevant projects

Key sources

1. Livingstone, S., Atabey, A., & Pothong, K. (2021). Addressing the problems and realising the benefits of processing children’s education data. Digital Futures Commission, 5Rights.

2. Hooper, L., Livingstone, S., & Pothong, K. (2022). Problems with data governance in UK schools: the cases of Google Classroom and ClassDojo. Digital Futures Commission, 5Rights.

3. Turner, S., Pothong, K., & Livingstone, S. (2022). Education data reality: The challenges for schools in managing children’s education data. Digital Futures Commission, 5Rights.

4. Livingstone, S., and Pothong, K. (Eds.) (2022) Education Data Futures: Critical, Regulatory and Practical Reflections. Digital Futures Commission, 5Rights Foundation.

5. Day, E., Pothong, K., Atabey, A., & Livingstone, S. (2022). Who controls children’s education data? A socio-legal analysis of the UK governance regimes for schools and EdTech. Learning, Media and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2022.2152838

6. Kidron, B., Pothong, K., Hooper, L., Livingstone, S., Atabey, A., & Turner, S. (2023). A Blueprint for Education Data: Realising children’s best interests in digitised education. Digital Futures Commission, 5Rights Foundation.

7. Livingstone, S., Hooper, L., & Atabey, A. (2024). In support of a Code of Practice for Education Technology. Digital Futures for Children centre, LSE and 5Rights Foundation.

8. Livingstone, S., Pothong, K., Atabey, A., Hooper, L., & Day, E. (2024) The Googlization of the classroom: Is the UK effective in protecting children's data and rights? Computers and Education Open. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2024.100195

9. Livingstone, S., and Pothong, K. (2022) What do children think of EdTech or know of its data sharing? Read our survey findings. Digital Futures Commission blog.

10. Stoilova, M., Livingstone, S., & Nandagiri, R (2020) Digital by default: children’s capacity to understand and manage online data and privacy. Media and Communication, 8(4).

11. Stoilova, M., Nandagiri, R., & Livingstone, S. (2019) Children’s understanding of personal data and privacy online – A systematic evidence mapping. Information, Communication and Society. Online first. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1657164

12. Stoilova, M., Livingstone, S., & Nandagiri, R. (2019) Children’s data and privacy online: Growing up in a digital age. London School of Economics and Political Science.

13. Pothong, K., & Livingstone, S. (2023). Children’s Rights through Children’s Eyes: A methodology for consulting children. Digital Futures Commission, 5Rights Foundation.

14. Day, E. (2021). The education data governance vacuum: why it matters and what to do about it. Digital Futures Commission, 5Rights Foundation.

15. Day, E. (2021). Governance of data for children’s learning in UK state schools. Digital Futures Commission, 5Rights Foundation.

16. Turner, S. (2024). Reality check on technology uses in UK state schools. Digital Futures Commission, 5Rights Foundation.

17. Livingstone, S. (2022). New report finds digital classrooms flout data protection law to exploit children’s data for commercial gain. Digital Futures Commission, 5Rights Foundation.

18. UNESCO. (2023). Global Education Monitoring Report 2023: Technology in education – A tool on whose terms? Paris, UNESCO

About the Digital Futures for Children centre

This joint LSE and 5Rights centre facilitates research for a rights-respecting digital world for children. The Digital Futures for Children centre supports an evidence base for advocacy, facilitates dialogue between academics and policymakers, and amplifies children’s voices, following the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child’s General comment No. 25.

Photo by A. Blum-Ross.